Pioneers of AI-Driven Art and the Future of Language - Andy Simionato + Karen Ann Donnachie

For over three decades, Andy Simionato and Karen Ann Donnachie have been at the forefront of computational art and design, consistently pushing the boundaries of creativity through technology. As an artist duo, their work delves into the intersection of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and the poetic possibilities of language and literature in a digitally transcendent age.

From custom-built, automated art systems to groundbreaking explorations of how emerging technologies shape human expression, their collaborations reflect a deep curiosity for how computation can evoke new emotions and ideas. This dynamic partnership has garnered widespread international recognition, winning prestigious awards and earning critical acclaim in both the art and design worlds.

Simionato and Donnachie's work has been exhibited across the globe and featured in major publications, positioning them as key figures in the conversation around the future of art, language, and technology. In this interview, we explore their journey, their artistic process, and how they envision the evolving relationship between creativity and AI.

TR: Your practice has focused on creating custom-built automated-art-systems driven by A.I. and machine learning. What sparked your initial interest in working with these technologies, and how do they shape the emotional or conceptual impact of your work?

Karen: I learned to code in my primary school years, where inputting even the simplest program to move a little turtle robot about on the floor of the classroom required hundreds of punch cards.

Andy: My first computer was the Commodore 64 my parents bought me in the early 1980s. Each month I would buy these (printed) magazines which had entire games in the form of code that I would type into the computer, one line at a time, before playing the game.

K: Both good examples of using computation to make something from, seemingly, nothing.

TR: You’ve been working together for over 30 years, evolving through various phases of technological and cultural change. How has your collaborative process changed over time, and what do you find most rewarding about this long-standing creative partnership?

A: We started working together while making experimental theatre in 1989. Sometimes we joke that in many ways we never really stopped making theatre. Stagecraft, scriptwriting, improvisation, even some illusionism seem to always be present in our work.

K: We began working creatively with digital media in the 90s. There was some resistance to these digital tools in those years, for example film was still considered the more “serious” medium in photography, so for important commissions we would keep a medium format (analogue film) camera in the centre of the studio set-up, as if it were the principle device, while secretly using small digital cameras to capture the images that would later make it into the publications (like Andy said, it’s all theatre!).

A: Eventually in 2001, frustrated with the difficulties of getting new media artworks published, we founded “This is a magazine” (also called “This is not a magazine”) which served as a space where we could share our experimental works intended for Internet browsers, as well as those from other artists working in that period, like Rafaël Rozendaal, Angelo Plessas…and many more.

TR: You’ve described your work as exploring "new feelings in an age of computational transcendence". Could you elaborate on what you mean by this, and how technology can evoke or transform human emotion through art?

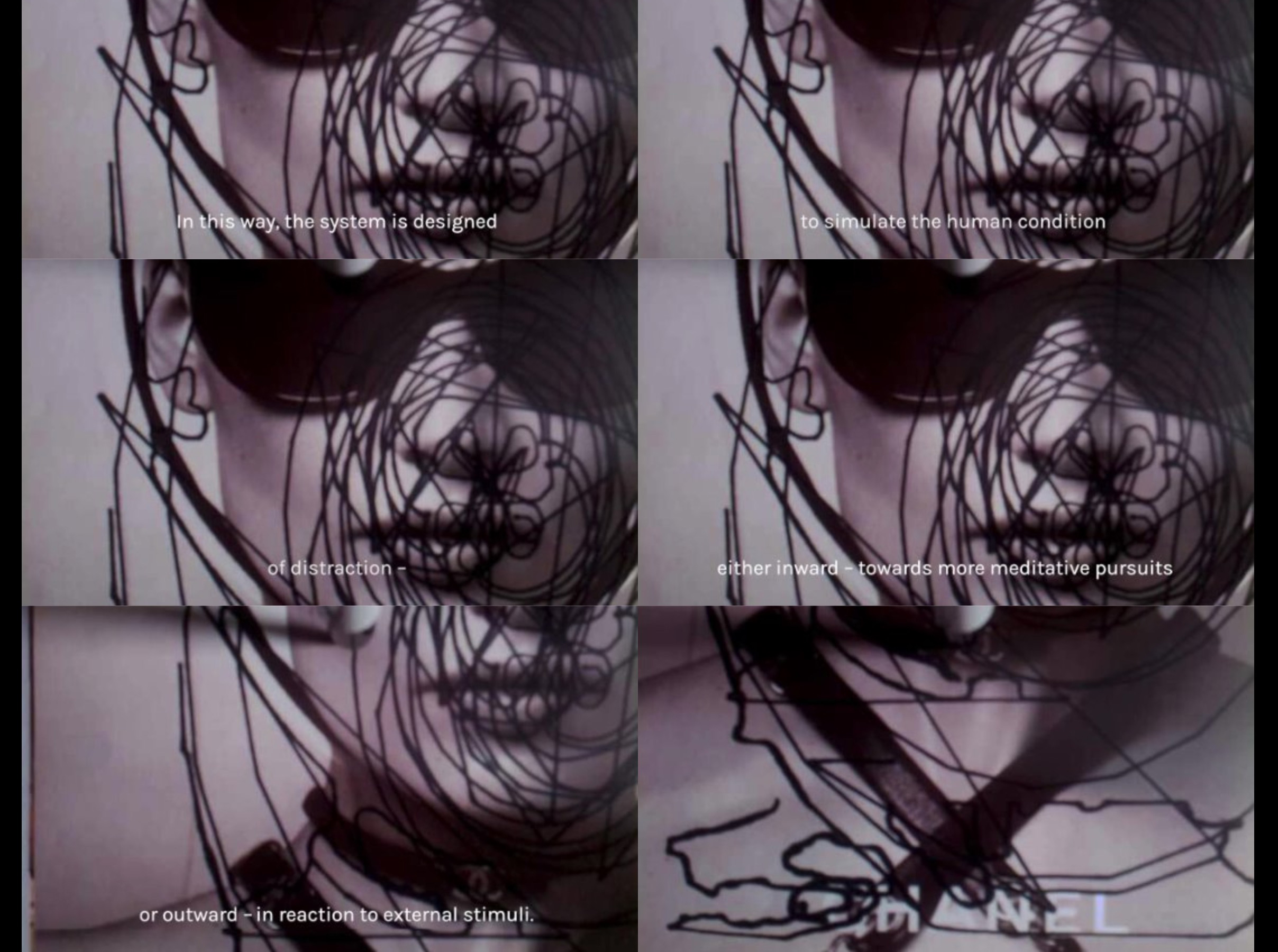

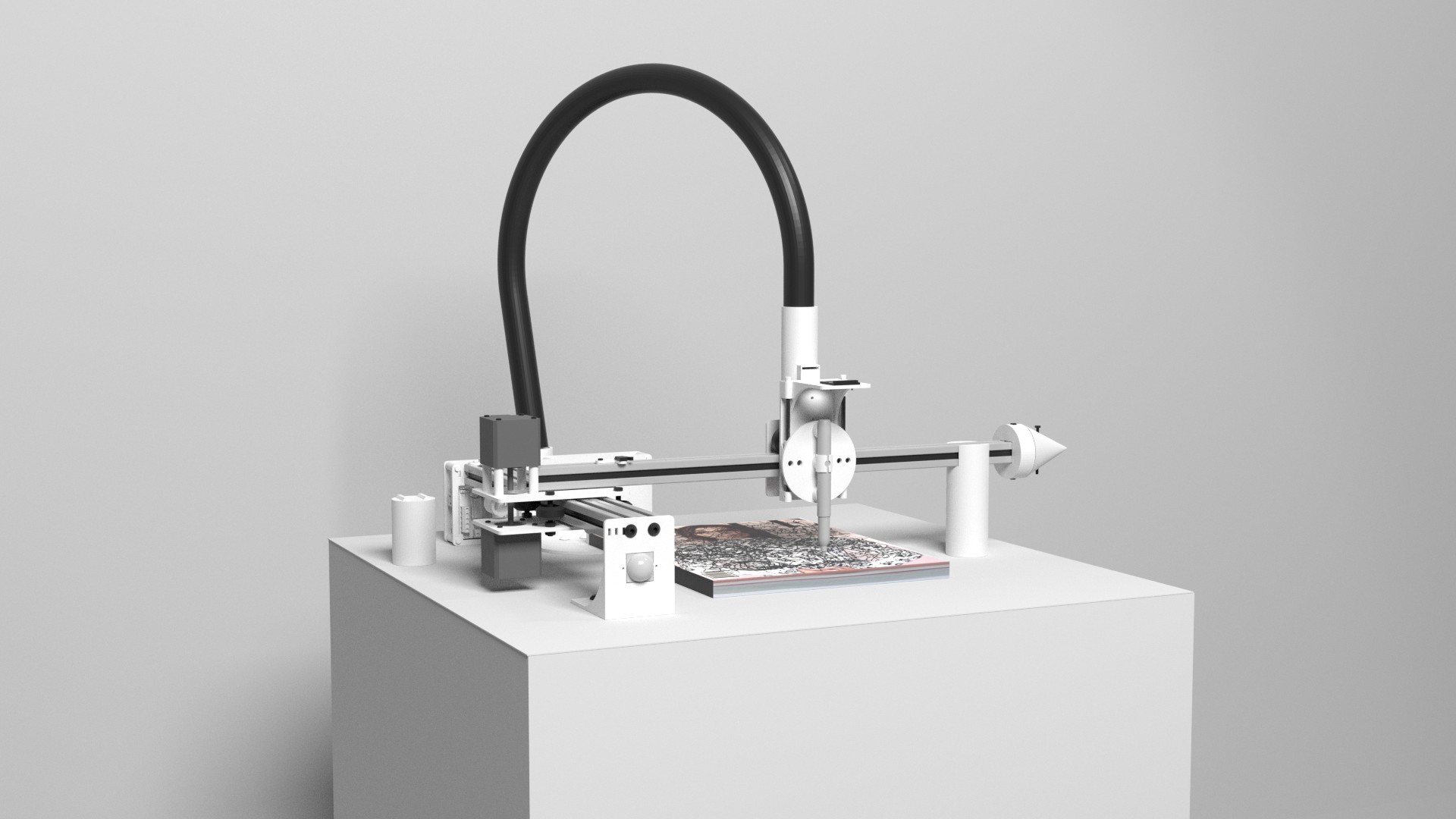

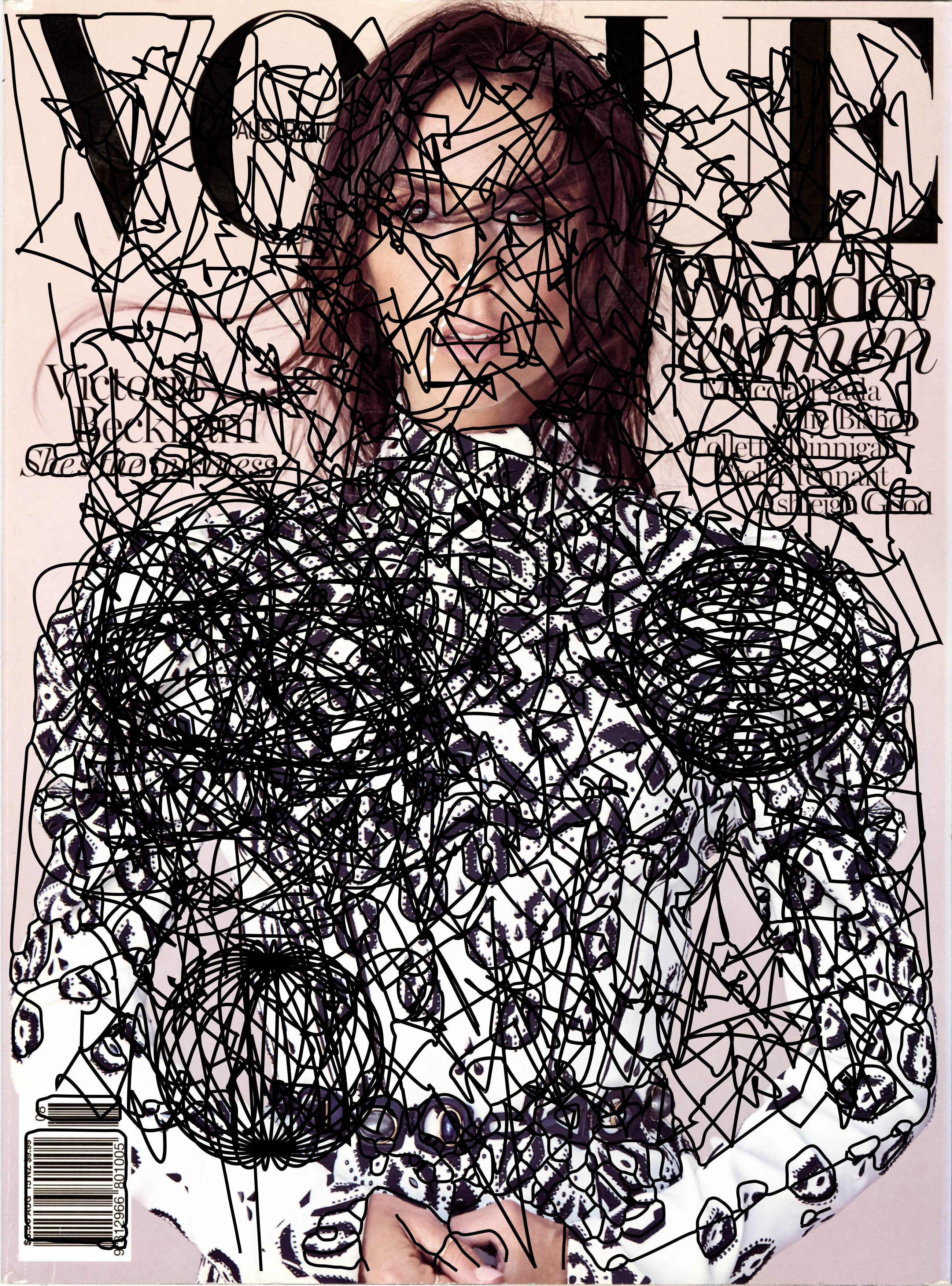

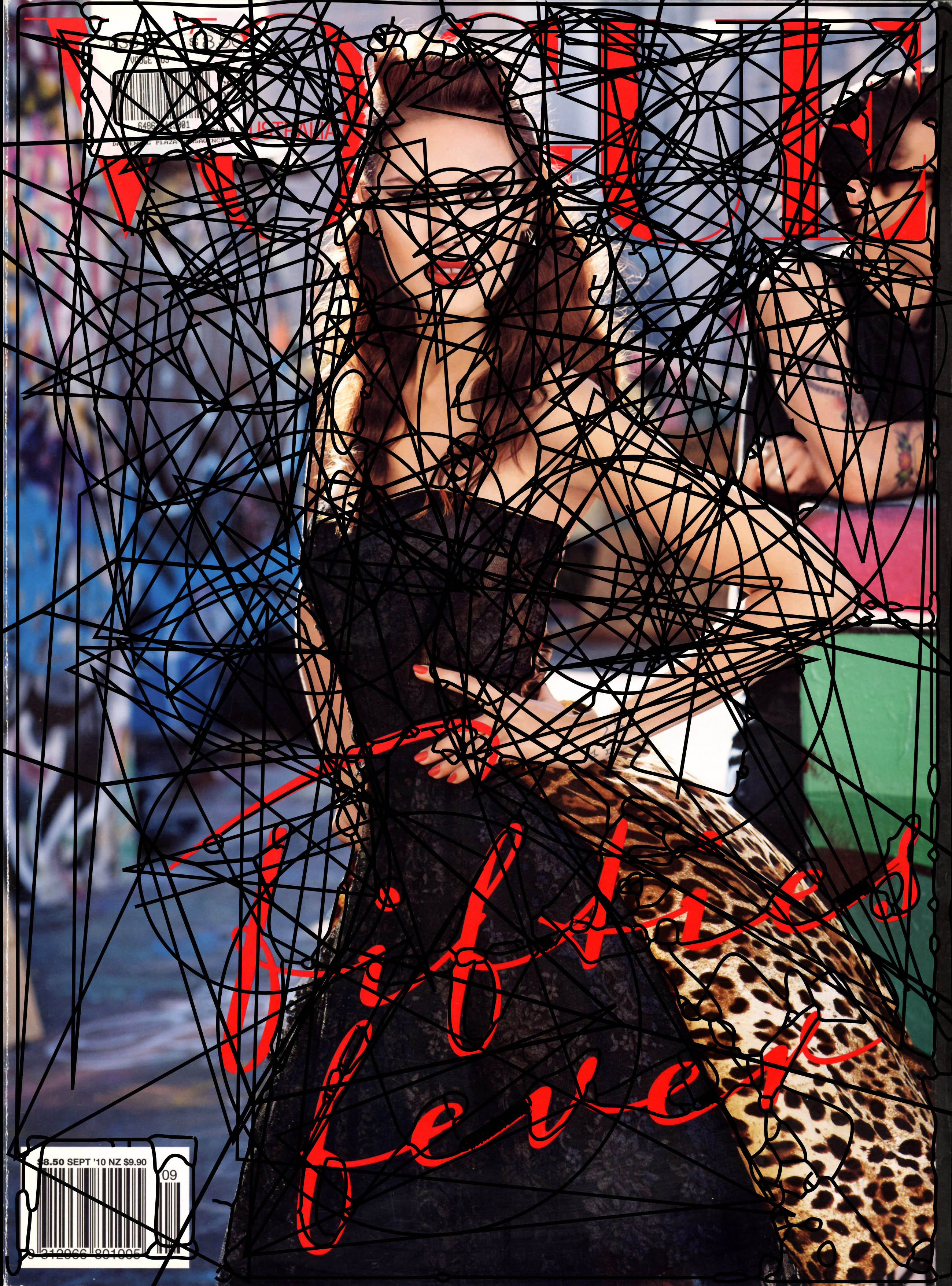

K: In the work ‘A Jagged Orbit’, we explore the benefits of designing so-called ‘intelligent’ machines with a capacity for ‘mind wandering’, daydreaming, and other forms of abstraction. As we started testing the system, we would feel unsure of what it was doing. These feelings of uncertainty, sometimes called the uncanny, emerge when the systems are sufficiently complex that we can’t predict, or even fully understand, its outcomes.

TR: Language and literature are recurring themes in your work. How do you see the intersection of language with A.I. and machine learning, and what excites you about the future of literary forms in a computational age?

A: Language is already a combinatorial machine. We leverage its potential within our automated-art-systems, for example in the nonhuman readings of books, which we consider post-digital publications which exist in the (late-age) of electronic literature.

K: Works like AI Seems to be a Verb, and The Library of Nonhuman Books, are explicitly intended to open up how we think about what’s next for language and books.

TR: Custom-built systems are central to your artistic practice. Can you share more about the technical side of this—how do you develop these systems, and what are some of the creative challenges you’ve encountered along the way?

(A+K): We begin with a prototype which we tinker with, hoping to uncover some experimental deviation, or unexpected outcome.

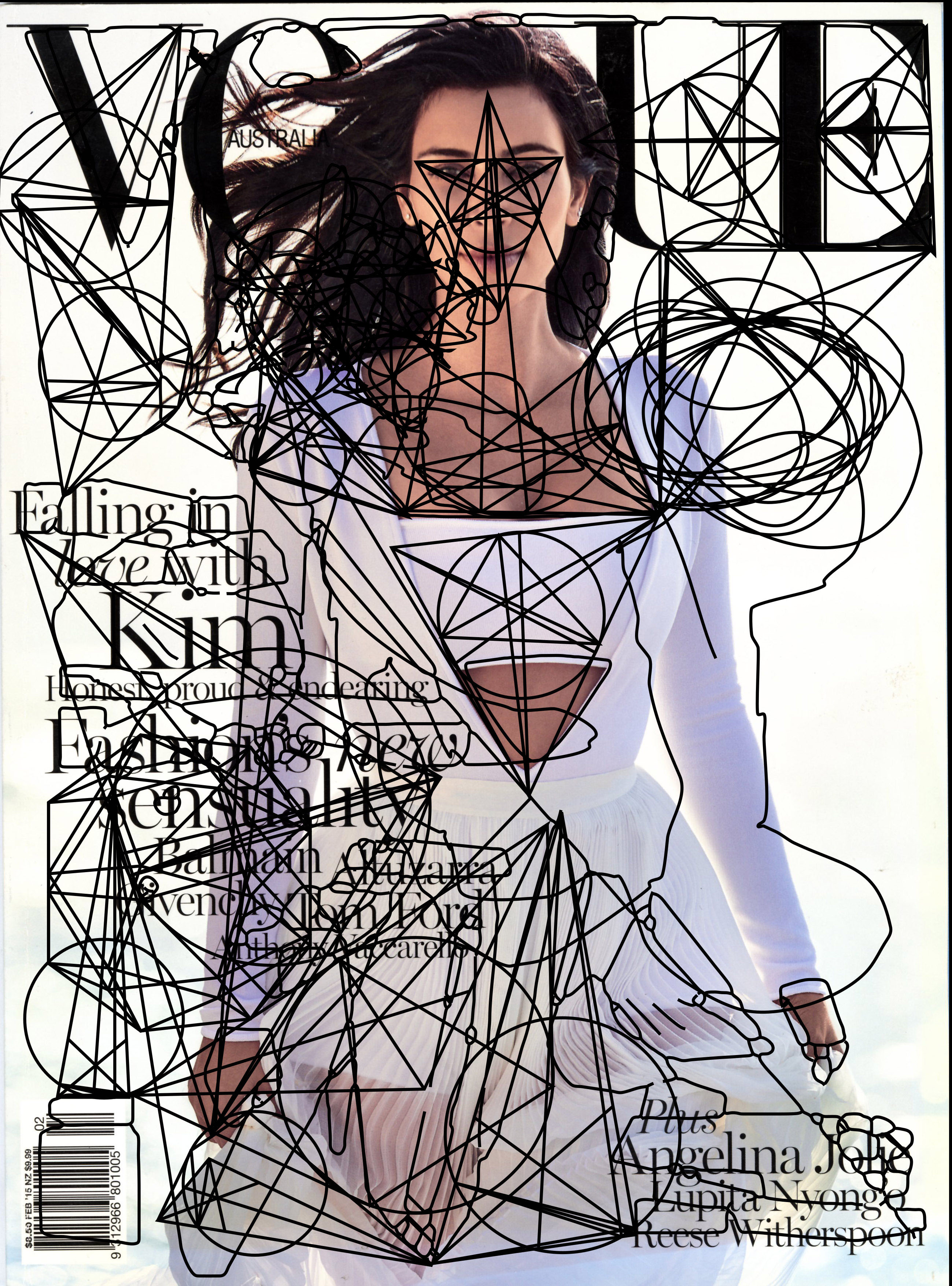

For example, an early prototype of A Jagged Orbit was a straightforward drawing machine running various algorithms originally developed by NASA to calculate orbital physics. During this experimental period we noticed the algorithm appeared to ‘doodle’ or at least, the orbit didn’t present as smoothly as we expected. We noticed it became increasingly difficult to discern if the algorithm was running correctly, so we began introducing deliberate ‘glitches’ to the system. This led us to consider how our own (human) behaviours associated with ‘work’ can also be difficult to distinguish at times, especially when we're thinking abstractly about a problem.

Once this feeling was identified, we proceeded to complete the system as it is today: an algorithm with two competing goals, the first attempts to draw orbital physics, while the second identifies and elaborates the images, making the system appear to become distracted.

TR: As computational artists, you navigate a complex space where code, machines, and creativity converge. Do you see A.I. as a collaborator in your work, and if so, how would you describe that relationship?

K: When code doesn’t work as expected we often joke that we should lean into ‘the agency of the machine,’ but we are quick to remind ourselves and others that AI is not a thing, nor a person, it is a process. AI is a verb.

TR: You've exhibited your work internationally and received numerous accolades. How do you think the global art world is responding to the intersection of art and technology, and what do you hope your work contributes to that dialogue?

K: This year we were grateful to have one of our ‘nonhuman reading’ machines commissioned for the German Museum of Books and Writing. Seeing the machine installed alongside some of the oldest books in European history opened up many new conversations with curators, librarians, and of course readers. This was really wonderful.

TR: In an era where automation and machine learning are rapidly evolving, what ethical considerations guide your practice, especially when it comes to the use of these technologies in art?

A: Certainly there are a number of concerns surrounding these technologies, specifically the extraction of human labour for their training, as well as controversies around the energy needs for their use.

K: We often describe our own use of these technologies through the lens of collage which foregrounds its processes and sources. So alongside the outcome of our automated-art-systems, we often show the machine with the original image or book, and any pieces of those images or books that the machine has removed or drawn over. Everything is laid bare.

A: Sometimes our workspace looks more like Dr Frankenstein’s operating table! But yes all the pieces are there, nothing is hidden.

K: This is one of the reasons we design and build our own systems, rather than use “black-boxed” technology (for example AI apps) where the user just enters a prompt without any real understanding of the processes involved (such as the provenance of the training data).

TR: What role do you think emerging technologies will play in the future of artistic expression, and how do you see your work evolving as these technologies continue to develop?

A: When we started out we found opportunities in the ‘home computer’ (because previously computers required dedicated rooms and teams of technicians) so ‘desktop publishing’ meant we could make an artwork, or design a book, which only a few years before would have required a series of professionals, and expensive equipment. Later the same thing happened with digital video and photography. In similar ways, the rise of technology like AI is introducing new opportunities for creatives. It would be hypocritical for us to deny that these tools, despite their inherent problems, will be fundamental for the next wave of artists and curators.

K: In recent years our work has aligned with technological advancements, but we were working with creative coding, Natural Language Processing and Computer Vision for many years before it was repackaged into AI. We will continue to explore new feelings emerging from this technology. To use the machine to make something from, seemingly, nothing.

TR: Looking ahead, are there any specific technological advancements or themes that you’re particularly interested in exploring in your future projects?

(A+K): We recently did a performance in Italy with a new system which improvises real time science-fiction film based on small found objects, typographic intertitles, and free-jazz music. But maybe this can be for the next email. Anyway, shortly we’ll put everything into >>> https://unknowing.cc/ .

Andy+Karen participated recently at Inscript Type Festival

Interview by: Giannis Papaioannou | Typeroom

Tags/ art, technology, future, creativity, artificial intelligence, design in motion

.gif)