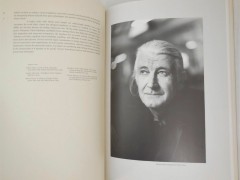

Bob Gill: a tribute to the feisty American design pioneer

"Take any idea or graphic direction as far as you can take it. And then, after you think you've taken it as far as you can, you'll find that you can take it further." That was Bob Gill's wisdom in words.

Graphic designer, illustrator, copywriter, teacher and author of many popular among designers books (i.e. "Forget all the rules you've learned", "Graphic Design Made Difficult" etc), Bob Gill (January 17, 1931 – November 10, 2021) was a true American legend in graphic design and beyond. For Gill, a master in conceptual creativity, "design is simply an organisation, everything else is rhetoric."

Gill attended Philadelphia Museum School of Art and Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art before starting a freelance career in New York. His early work included illustrations for Esquire, Architectural Forum, Fortune, Seventeen, The Nation, children’s books and film titles.

Although Alexey Brodovitch told him to forget design and be a photographer, the iconic Paul Rand, suggested him to "stay in this business." Luckily he did.

#bobgill

— ThePrintArkive (@ThePrintArkive) November 10, 2021

1931 – 2021

Well, this evening I learned that Bob Gill passed away this week - another #legend lost!

The image is lifted from a booklet announcing the formation of #fletcherforbesgill back in 1962. pic.twitter.com/nt4z3iQhBw

Having won his first ADC Gold Medal for the title card he designed for the Private Secretary CBS sitcom, Gill started teaching at the School of Visual Arts in 1956, always looking for an idea, not a concept.

A film title designer in several films, Gill moved to London in the swinging sixties. April Fool's Day, 1962, Gill, Alan Fletcher and Colin Forbes established Fletcher/Forbes/Gill design studio, the forerunner of Pentagram.

An artist at heart, Gill returned to New York in 1975 to write and design Beatlemania -the largest multi-media musical up to that time on Broadway- and he never stopped exploring the many creative aspects of one's life.

One of the founders of the Designers and Art Directors Association (D&AD) and an avid author on design, Gill strongly believed that designers are the original problem solvers.

For Gill research, lots of it, was crucial to the creative process and good design is "what communicates best in original way, that says exactly what you want it to say. Not the design that just looks good."

From designing a proposed peace monument for Times Square, to collaborating on a Broadway musical to directing hardcore pornography not his was off-limits for Gill who packed many careers into one. Gill received the highest accolades from several Art Directors Clubs including the New York Art Directors Club Hall of Fame and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the D&AD Association of London.

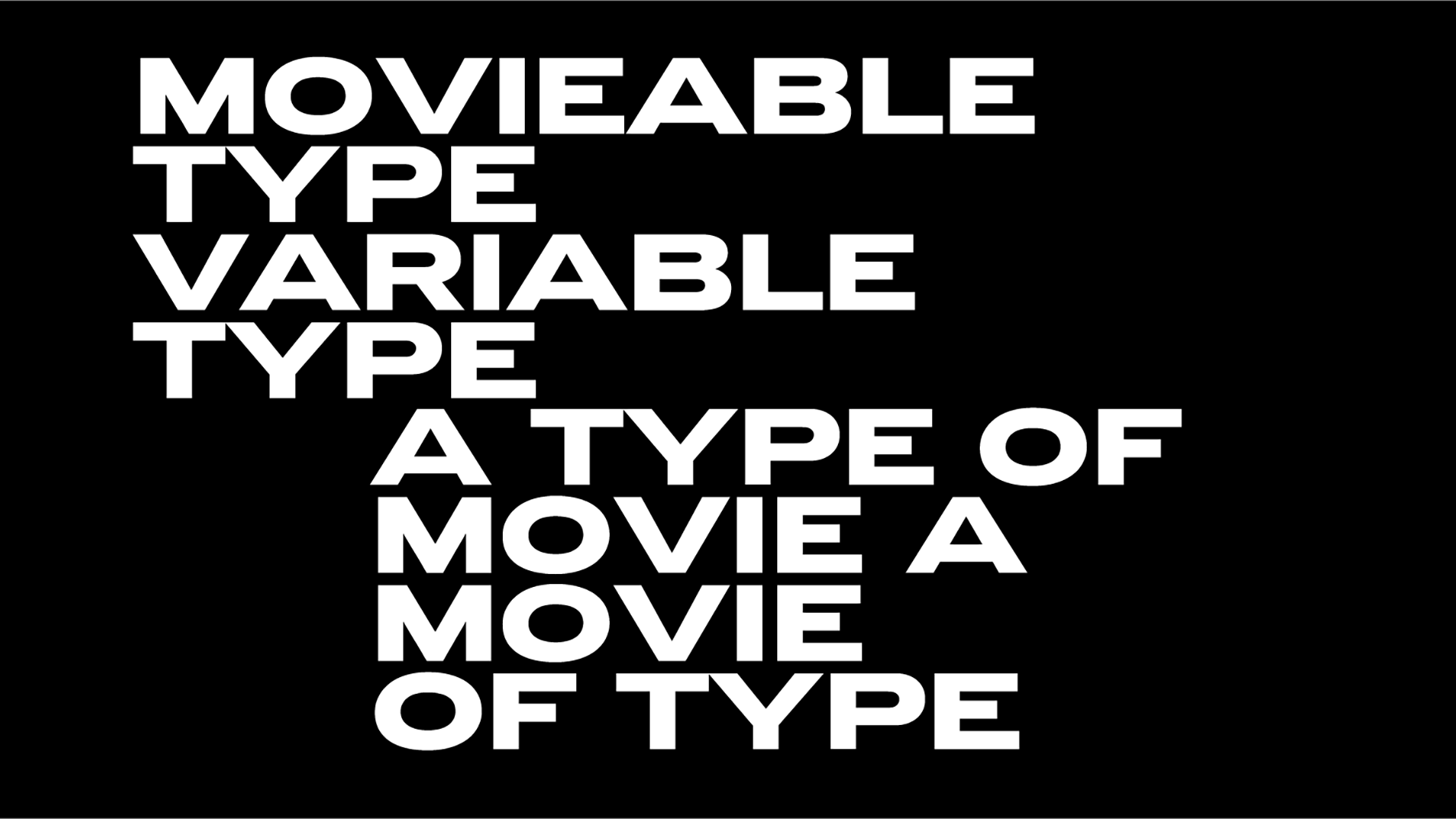

An oft-quoted design legend who always advocated for a no-nonsense approach to problem solving, this is one of Bob Gill's design manifestos, written for "Manifesto, A Collection of Designers’ Credos" exhibition curated by Tankboys and published in the accompanying book back in 2009.

"The audience for graphic design is the same audience that will have seen the latest alien movie and the hottest music video with special effects that are absolutely dazzling. How can a graphic designer compete with this magic? We don’t have the technology or the budgets, or the time. If we want to attract attention to our work, we have to go to the other extreme. We have to go to reality! We must take a careful look at the real world and, in effect, say to our audience, 'Look! have you ever noticed this before? Even though it was right under your nose.' That, to me, is more exciting than the most amazing special effects. And there’s another thing about the situation today that graphic designers must recognize. Before computers, the production of printed matter was in the hands of designers and printers. Most clients had only the vaguest idea how it was produced. And they were prepared to pay well for their logos, newsletters, brochures and other business paper.

Now, for very little money, it’s possible to buy a program which allows anyone with a computer to produce most of the stuff for the average business. The mystique has finally gone out of ordinary design and print. These programs fit words and images into slick professional looking formats. And for low-end commercial needs, that’s perfectly fine. So, if a typist can do much of the work previously done by well-paid specialists, what’s left for the designer? Designers have to do things that a typist with a computer can’t do. This means that they have to be problem solvers, if they are to survive. And, unfortunately, thinking is not the designer’s first love. They love choosing colors, pushing type and shapes around, drawing in a particular style and imposing the latest graphic tricks on their next job, regardless of whether they are appropriate or not.

They get these tricks from the culture. Most designers spend their time trying to emulate what’s supposed to be hot, what’s current, what’s trendy. But just think, if we want to do something the computer in the hands of a non-designer can’t do, something that’s original, how can we rely on what the culture tells us? (The culture tells all of us the same thing.)

A few mega-corporations inflict this culture on us. Their virtual monopoly of TV, fashion, pop and rock’n’roll music, cable, theatre, magazines and film, etc., is designed to appeal to the lowest common denominator which, in turn, allows them to merchandise the most stuff: Obama action figures and Kelly Clarkson t-shirts, for example. Of course, the establishment allows just enough high culture to prove that they’re not only Philistines. How can you extricate yourself from this avalanche of white-bread, so that you can be an original thinker? First purge your mind of as much cultural baggage as possible. When you get a job, regardless of how familiar the subject, resist any temptation to think you know enough about it, and that you’re ready to design. Assume that all of the information and imagery was supplied by the culture, that none of the information or imagery is original.

Research the subject as if you know nothing about it. And don’t stop until you have something interesting, or even better, something original to say. That’s the most likely way of producing an original image. The design process can begin only after you are satisfied with the statement. Listen to the statement. It will design itself. Well, almost. As there are trillions of images assaulting your audience, competing for their attention, the least you can do is not have the words and images in your design competing with each other. Take a statement like, 'we cure cancer for one dollar.'

It isn’t necessary to make those words look interesting. They are interesting. If you try to make interesting words look interesting, the way they look competes with their meaning. Also, if you want to draw attention to an interesting image, the words that accompany it shouldn’t be unusual. Design is problem-solving. Most designers are not very interested in problem-solving. They’re more interested in producing work that looks good. That’s like the mathematician who, before knowing the problem, knows that the answer is 128. Designers who know their solution must consist of lots of white space, and a particular typeface, etc., before they know the problem, are just like the mathematician who knows that the answer is 128. What is good design is what communicates best in an original way, even though it doesn’t conform to our preconceptions of good design.

No image or color or typeface is always good or always bad. What makes it good is if it’s the best image or color or typeface that says exactly what you want to say.

Otherwise forget it.

All the best. Bob Gill"

Tags/ graphic design, illustrator, pentagram, paul rand, school of visual arts, bob gill

.jpg)