Can a font, in itself, truly be racist? CNN & more report on “chop suey” fonts

“Ethnic type — not just chop suey but all of the varieties — survives for the simple reason that stereotypes, though crude, serve a commercial purpose. They are shortcuts, visual mnemonic devices” writes Paul Shaw in Print magazine. His commentary on the many stereotypes hidden in plain sight is as relevant as ever.

Ethnic typefaces are decorative typefaces that have been designed to represent characters of the Roman alphabet but at the same time evoke another writing system. This group includes typefaces designed to appear as Arabic, Chinese characters (Wonton fonts), Cyrillic (Faux Cyrillic), Indic scripts, Greek (an example being Lithos), Hebrew, Kana, or Thai. These are used largely for the purpose of novelty to make something appear foreign or to make businesses offering foreign products, such as restaurants, clearly stand out. This typographic mimicry, also known as a faux font (named faux x, where x is usually a language script), pseudoscript, mimicry typeface, simulation typeface or a “foreign look” font is still in use.

“But these fonts are practically free from scrutiny and widely accepted. While much research in visual sociology has been done on gender and racial portrayals of advertising, almost all of it has focused on images, and not the importance of fonts. And fonts really are just as important after all ‘typography is what language looks like’” notes Nichole Fernández quoting Ellen Lupton’s must-read book Thinking With Type.

It is evident that typography evokes emotions, that in a visual over-saturated culture we live and breathe type, we guzzle letterforms and shapes of numerous connotations. Eventually, in times of bigotry, the racialization of type matters as long as we provide room for nuance in the context.

Delving into the matter, Linus Boman, “a type nerd and veteran designer” who makes videos in the intersection of pop culture and graphic design and Raven Mo, a New York-based designer specializing in brand identity and type explore how chop suey fonts, a subcategory of so-called “ethnic” display fonts, and a unique American invention with roots in the 170-year history of Chinese migrants in the United States became the face of Chinese food in America.

“Many Americans have probably seen chop cuey fonts on Asian restaurant signs, takeout boxes and fortune cookies. It has a distinctive style of wedge-like shapes, and is supposed to invoke Chinese calligraphy. But if you grew up in China like me, chances are these fonts would be totally foreign to you” notes Mo who presented her work with Boman in her recent TypeLab presentation.

In the insightful video, the duo analyzes the font, unpacks its history, and deconstructs its design putting things into a long-overdue perspective.

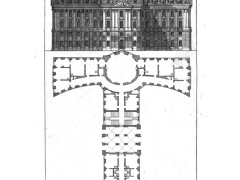

“…After the 1906 earthquake destroyed San Francisco’s Chinatown, it had to be rebuilt from the ground up. For the redesign, an architect and an engineer were hired who had never visited China. They built exaggerated Chinese architecture that referenced temples from the Song Dynasty, a period in Chinese history that occurred during the middle ages. …Where the dragon gates and pagoda roofs went, the chop suey font was sure to follow” they explain.

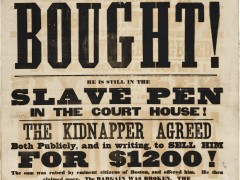

“If typography is a voice, what is this type but a fake foreign accent?…. Sadly, it also has an equally long history of being used to mock and otherize people of Asian descent….While Chinese migrants spread the use of Chop suey fonts, this font was never created by them. It was part of an outsider-created makeover that helped their economic survival during a time when they were the targets of suspicion and discrimination. The typographic caricature was one minor insult among many for first-wave migrants. When fighting for basic human rights, authentic cultural expression is a luxury” comments Mo.

Following is an excerpt from the CNN article written by Anne Quito on the many typographic stereotypes we must abolish:

“In 19th-century Germany, using a calligraphic blackletter typeface called Fraktur was considered as an expression of nationalism. German books were printed in this gothic-style font, despite being hard to read. The Nazi party then embraced Fraktur -- it was even used on the cover of Adolf Hitler’s manifesto, ‘Mein Kampf’ -- before suddenly banning the font in 1941 and categorizing it as Judenlettern (‘Jewish letters’).

Yet, there are also examples of fonts harmlessly evoking national or regional pride. Take the distinctive Euskara lettering, used throughout the seven provinces of the Basque County, and deployed on everything from monuments to restaurant menus. The ‘large-footed, big-eyed, Roman-styled characters,’ as a 19th-century chronicler of the region's monuments once described them, emerged during the pinnacle of Basque nationalism in the late 1800s.

It’s worth noting that, in 1930s America, some Chinese immigrants themselves used chop suey fonts on their restaurant signs, menus, and advertisements, as a way to heighten the exotic appeal of their establishments.

And ‘Oriental simulation fonts’ (or letterforms designed with aesthetic markers of a particular culture) didn't just approximate Chinese calligraphy. Decorative fonts like El Dorado or Taco Salad were designed to represent Mexico. The same goes for the Pad Thai font, which borrows strokes from the Thai script. Similarly, there are a host of crude, hand-drawn fonts purporting to capture the aesthetic of the entire African continent.

Shaw said that the persistence of ethnic types, as offensive as they appear to some, lies in their graphic efficiency. They survive ‘for the simple reason that stereotypes, though crude, serve a commercial purpose,’ he wrote. ‘They are shortcuts, visual mnemonic devices. There is no room for cultural nuance or academic accuracy in a shop’s fascia.’

A Nazi font banned by Nazis? Fraktur and its legacy in the must-listen design podcast of this week

….

‘We need to democratize the education of type design across different ethnic and economic, socioeconomic backgrounds,’ said Tom Rickner, creative director at Monotype. ‘There’s work to be done there, but it’s happening. The right way forward is to have bilingual, trilingual, even multilingual typography,’ he added, suggesting that Chinese restaurant menus could perhaps, be presented in both English and (either simplified or traditional) Chinese characters” reads CNN’s report.

“For many designers ethnic fonts are seen as simply ‘garbage fonts’ used by ‘amateur designers’…. But amateur or not, we go about our day exposed to way more than the rare professional high-end sleek design with a social consciousness. We see these stereo‘types’ everywhere. Maybe it is time we hold designers accountable for these stereotypes. Maybe we should also hold accountable the institutions that teach design without teaching the social implications of design. The job of a designer is not to be uninventive, simply repurposing stereotypes for easy visual communication. We need to call on the design industry to be innovative, creative, and to generate useful visual solutions, because ultimately, that is their job” concludes Fernández.

Type designers should, by default, celebrate languages and cultures via design means. But, can a font truly be racist? As this long-running debate keeps going strong, let’s pause for a second, and address the importance of education in type design in full frame whilst not blaming the fonts for racism. The real racists that we should stand up against are the ones that walk and talk bringing humanity to the verge of hate.

Tags/ typography, typefaces, fonts, cnn, print magazine, chinese, typedesign, paul shaw, migrants, raven mo