Inked: the story of typography's earliest material & the eco-friendly challenge to know

If you think ink is no big deal, think about this: How would you like to carry a backpack full of stone books to school every day? Before ink was invented, people wrote pretty 'heavy' messages to each other. They carved pictures and letters into stone or pressed them into wet clay” notes Sharon J. Huntington. With ink being the theme for Design Museum's weekly typographic fest on Twitter aka Font Sunday, Typeroom delves into the origins of ink and the importance of eco-friendly alternatives to a material linked to type in more ways than imagined.

Ink is a liquid or paste that contains pigments or dyes and is used to color a surface to produce an image, text, or design. Ink is also used for drawing or writing with a pen, brush, or quill whilst thicker inks, in paste form, are used extensively in letterpress and lithographic printing.

Ink can be a complex medium, composed of solvents, pigments, dyes, resins, lubricants, solubilizers, surfactants, particulate matter, fluorescents, and other materials. The components of inks serve many purposes; the ink's carrier, colorants, and other additives affect the flow and thickness of the ink and its dry appearance.

In 2011 worldwide consumption of printing inks generated revenues of more than 20 billion US dollars. Demand by traditional print media is shrinking, on the other hand, more and more printing inks are consumed for packagings

Ink is linked to humanity's history since ancient times as many cultures around the world have independently discovered and formulated inks for the purposes of writing and drawing. The knowledge of the inks, their recipes and the techniques for their production comes from archaeological analysis or from written text itself.

The earliest inks from all civilizations are believed to have been made with lampblack, a kind of soot, as this would have been easily collected as a by-product of fire.

Ink was used in Ancient Egypt for writing and drawing on papyrus from at least the 26th century BC while Chinese inks may go back as far as three or even four millennia, during the Chinese Neolithic Period. These used plants, animal, and mineral inks based on such materials as graphite that were ground with water and applied with ink brushes.

Tintenstrich eines Füllers bei ca. 50-facher Vergrößerung, 2006, Tobias R. – Metoc via Wikipedia

Direct evidence for the earliest Chinese inks, similar to modern inksticks, is around 256 BC in the end of the Warring States period and produced from soot and animal glue. India ink was first invented in China, though materials were often traded from India, hence the name. The traditional Chinese method of making the ink was to grind a mixture of hide glue, carbon black, lampblack, and bone black pigment with a pestle and mortar, then pouring it into a ceramic dish where it could dry. To use the dry mixture, a wet brush would be applied until it reliquified. The manufacture of India ink was well-established by the Cao Wei Dynasty (220–265 AD).

The practice of writing with ink and a sharp-pointed needle was common in early South India and several Buddhist and Jain sutras in India were compiled in ink. In ancient Rome, atramentum was used; in an article for the Christian Science Monitor, Sharon J. Huntington describes many other historical inks.

About 1,600 years ago, a popular ink recipe was created. The recipe was used for centuries. Iron salts, such as ferrous sulfate (made by treating iron with sulfuric acid), were mixed with tannin from gallnuts (they grow on trees) and a thickener. When first put to paper, this ink is bluish-black. Over time it fades to a dull brown.

Scribes in medieval Europe (about AD 800 to 1500) wrote principally on parchment or vellum. One 12th century ink recipe called for hawthorn branches to be cut in the spring and left to dry. Then the bark was pounded from the branches and soaked in water for eight days. The water was boiled until it thickened and turned black and wine was added during boiling. The ink was poured into special bags and hung in the sun. Once dried, the mixture was mixed with wine and iron salt over a fire to make the final ink.

The earliest inks from all civilizations are believed to have been made with lampblack, a kind of soot, as this would have been easily collected as a by-product of fire

The reservoir pen, which may have been the first fountain pen, dates back to 953, when Ma'ād al-Mu'izz, the caliph of Egypt, demanded a pen that would not stain his hands or clothes and was provided with a pen that held ink in a reservoir.

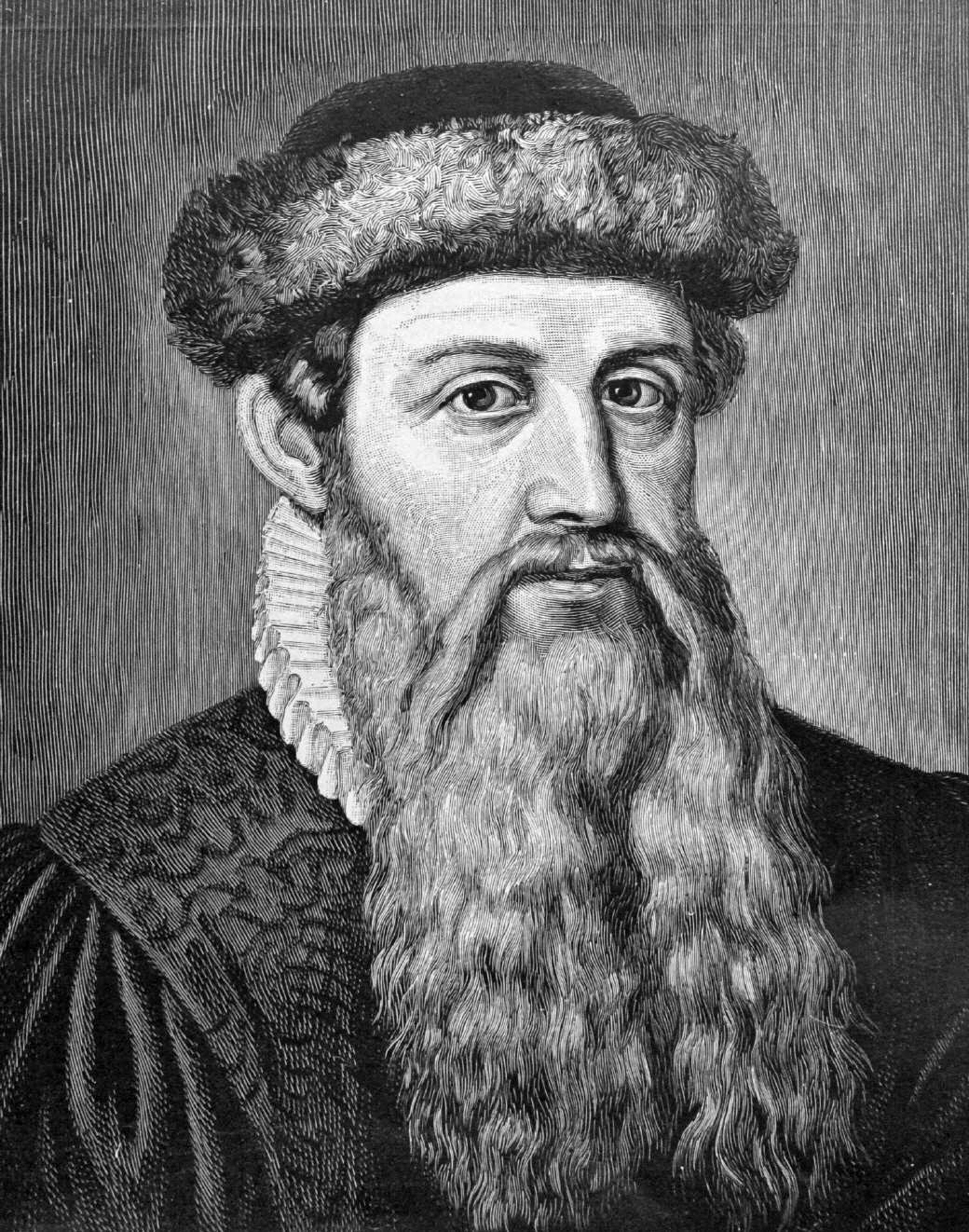

In the 15th century, a new type of ink had to be developed in Europe for the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg. According to Martyn Lyons in his book Books: A Living History, Gutenberg's dye was indelible, oil-based, and made from the soot of lamps (lamp-black) mixed with varnish and egg white.

Two types of ink were prevalent at the time: the Greek and Roman writing ink (soot, glue, and water) and the 12th-century variety composed of ferrous sulfate, gall, gum, and water. Neither of these handwriting inks could adhere to printing surfaces without creating blurs. Eventually an oily, varnish-like ink made of soot, turpentine, and walnut oil was created specifically for the printing press.

The best inks for drawing or painting on paper or silk are produced from the resin of the pine tree. They must be between 50 and 100 years old. The Chinese inkstick is produced with a fish glue, whereas Japanese glue ("nikawa") is from cow or stag.

The quest for better ink

On the downside of it, ink is often toxic if swallowed, depending on the material and pigments that the ink is made from, causing headaches, skin irritation and damage to one’s nervous system. Furthermore, inks often use up precious non-renewable oils and heavy metals, which both have a negative impact on the environment but a variety of environmentally-friendly inks might save the day making our printing habits sustainable and green.

Traditional inks often emit Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC) which can be both a health hazard to print works and a pollutant to the ozone, but eco-friendly inks do nothing of the kind.

There is a variety of environmentally-friendly inks, from UV ink, soy-based ink which is made from soybeans as opposed to a petroleum-based ink and is already a hit as corporate sustainability becomes more mainstream and eco-solvent ink, a form of non-water based ink made from ether extracts taken from refined mineral oil.

When using vegetable-based inks, the print industry reduces the demand for petroleum-based products and eco-friendly ink is a very important component of green printing -along with printing on recycled paper and tree-free paper.

“What is expected from printing ink is quality, being trouble-free, economical, and efficient. Because vegetable and mineral oil-based inks show similar printing performances on coated and uncoated papers in terms of printing quality, the determinant for ink choice should be the environment and health” noted Cem Aydemir, Semiha Yenidogan, Arif Karademir, and Emine Arman Kandirmaz in “The examination of vegetable- and mineral oil-based inks’ effects on print quality,” published in the Journal of Applied Biomaterials & Functional Materials.

“There are many potential economically-viable alternatives to petrochemical-based polymers, but you have to look at the whole lifecycle”

In this task to innovate for good Xerox's Agent of Change, Guerino Sacripante, a polymer scientist at Xerox Research Centre of Canada, feels a "deep personal responsibility to reduce our reliance on fossil fuels" notes Xerox.

“As a polymer scientist at Xerox’s Research Centre of Canada (XRCC), Guerino has dedicated his 30-year career to finding more efficient ways to print. In that time, he’s become one of Xerox’s most prolific innovators, receiving over 240 patents for his work on new toner compounds and printing processes. 'Most Xerographic machines today use dry toner powder made up of tiny plastic particles,” Guerino explains. “That plastic is derived from fossil fuels that are abundant now, but will start to run out. The particles have to be heated up until they melt, and that consumes energy. Then the melted plastic limits the recyclability of the printed matter. The whole lifecycle puts stress on the environment' he says of his challenge of making print both sustainable and commercially viable.”

“The challenge is to get the material, make it, and still offer it at the same price,” he says. “There are many potential economically-viable alternatives to petrochemical-based polymers, but you have to look at the whole lifecycle. When I look back at what I’ve done in life, I want to be able to say I’ve done something positive for humanity. If I can actively help us move away from fossil fuels, that will be a tangible contribution that makes things better for everyone”.

Following are some of our favorite entries in this week's Font Sunday, seriously inked typographic fest.

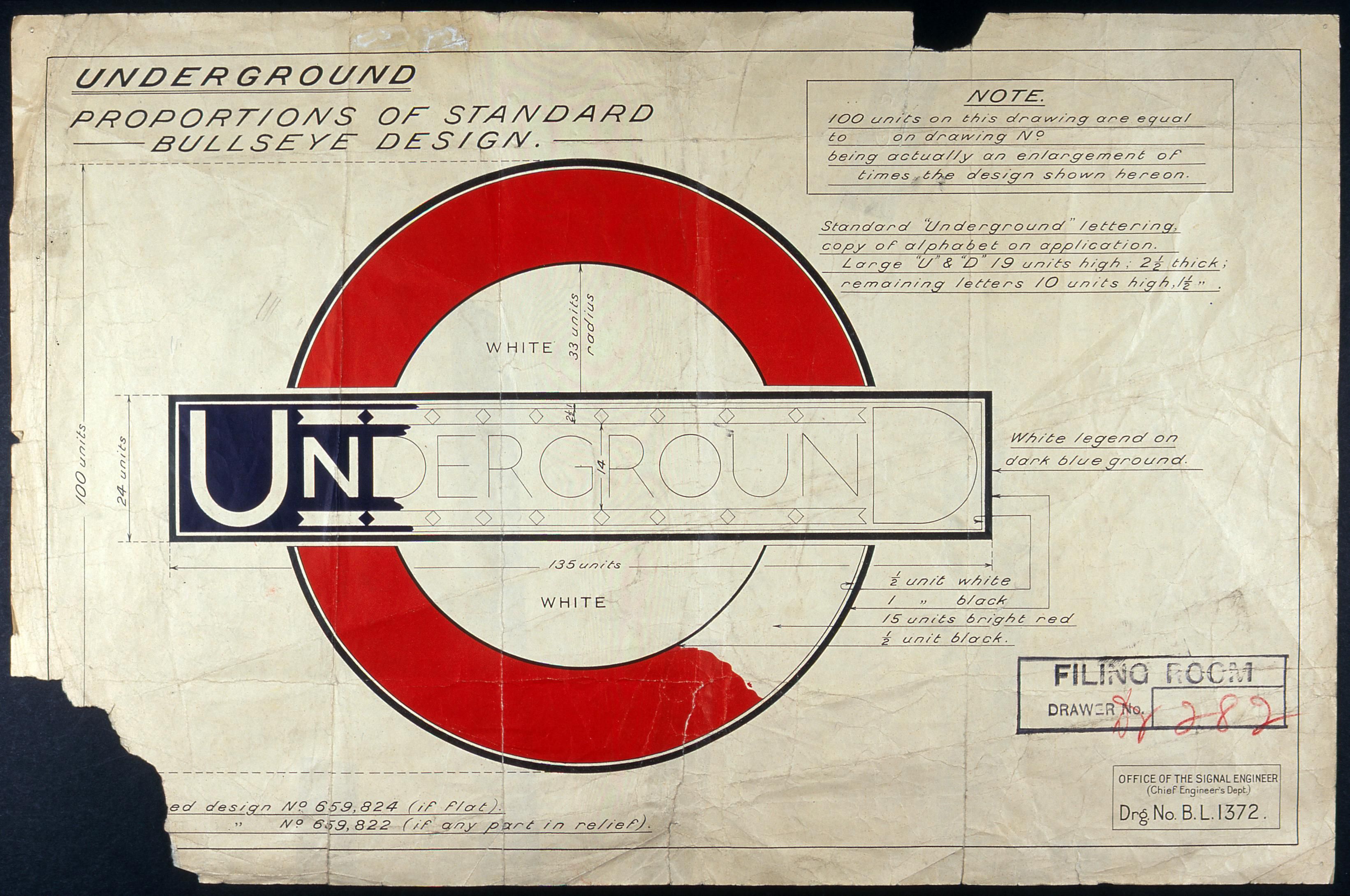

The London Underground roundel and typeface as drawn in 1920 by Edward via @Birmingham_81

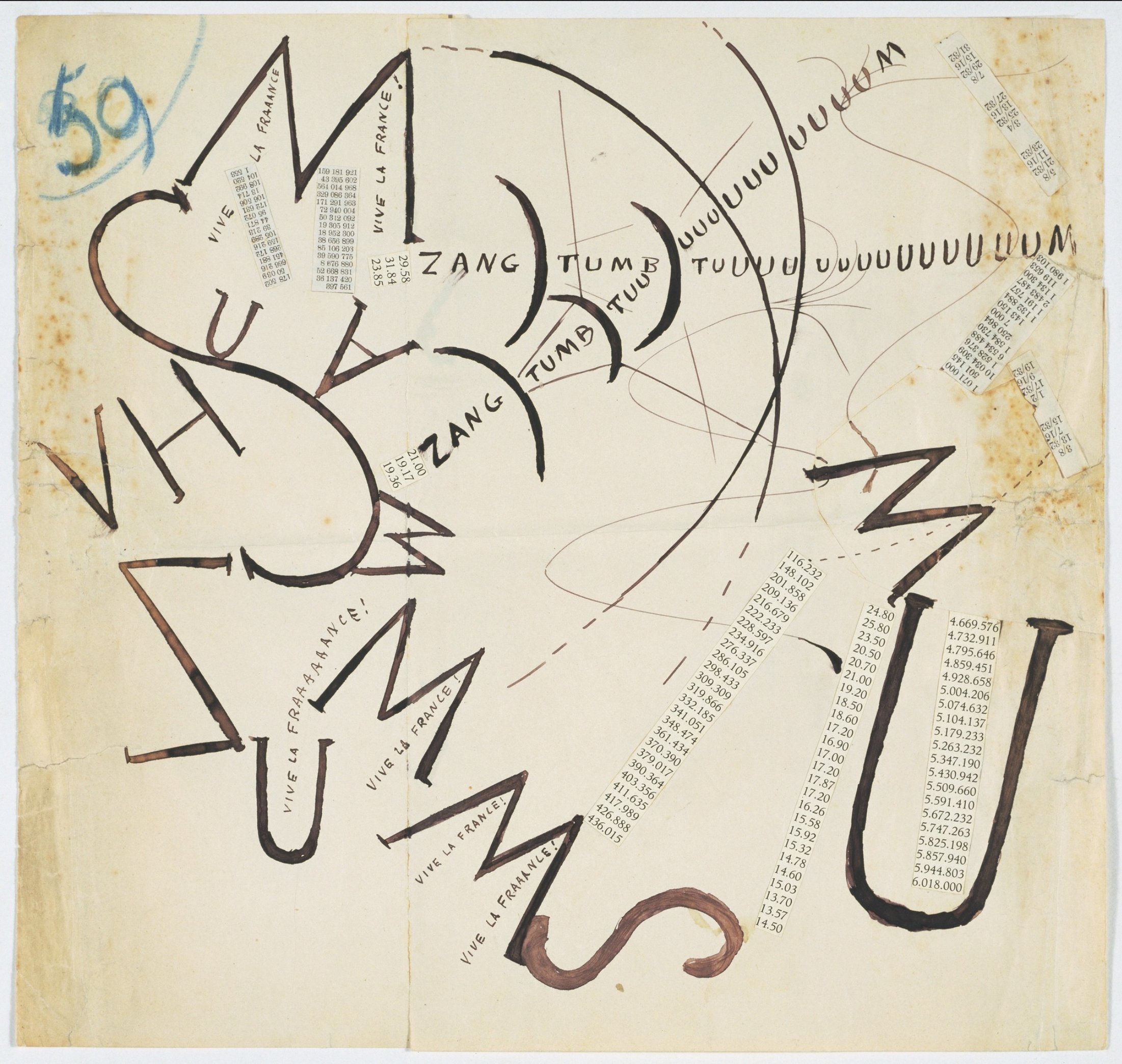

'Vive la France' by the founder of the Futurist movement, Filippo Marinetti, 1914-15 via @andrewbannister

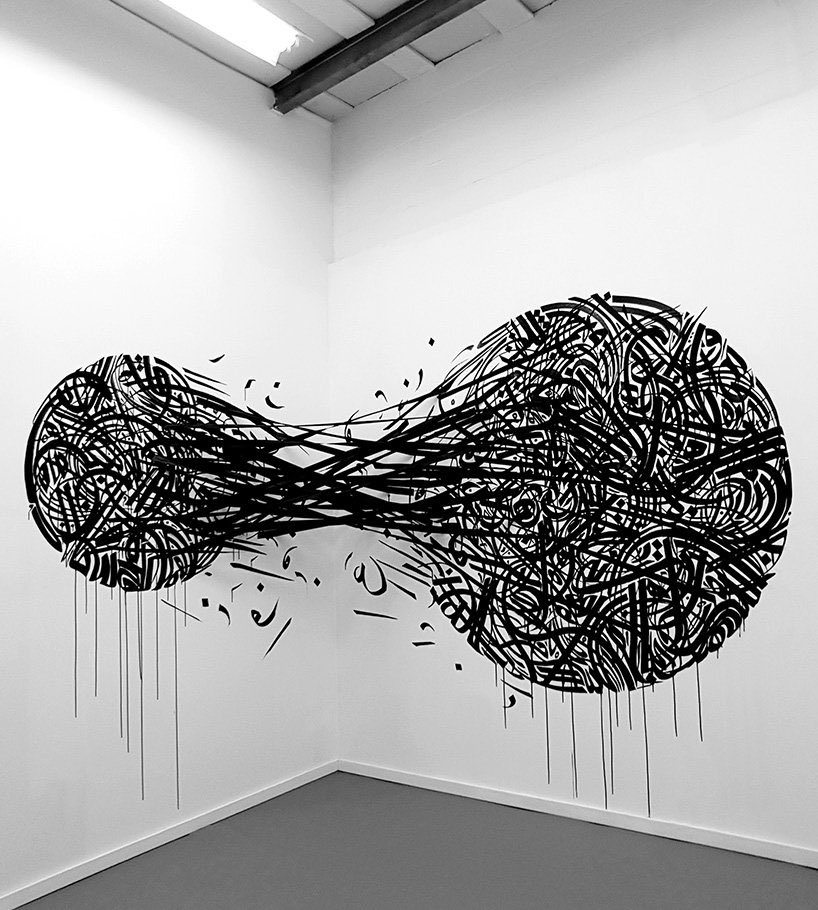

Sasan Nasernia Driping Calligraphy 2019 via @Dazarbeygui

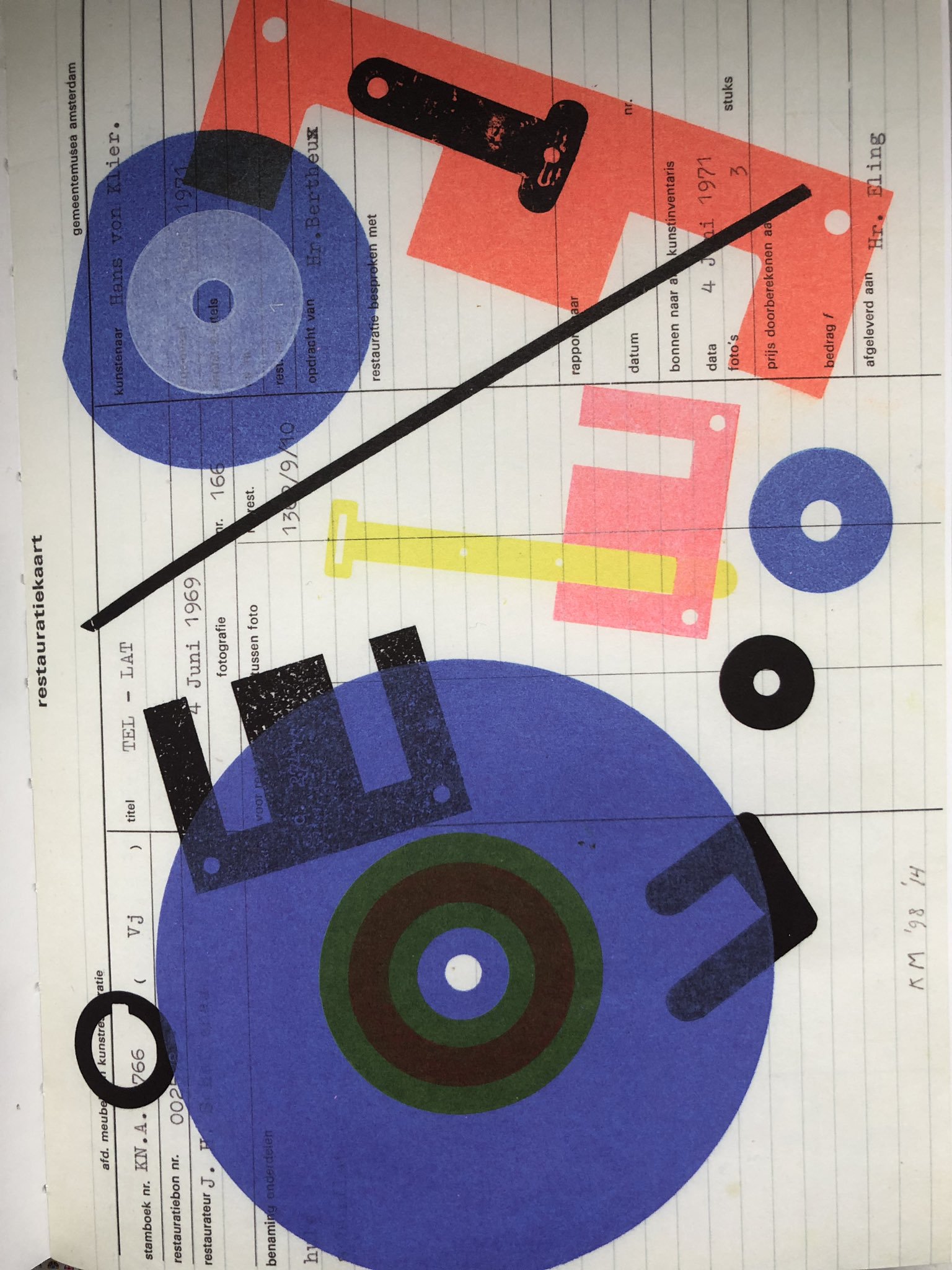

All sorts of ink from printing workshop master Karel Martens via @lara_hanlon

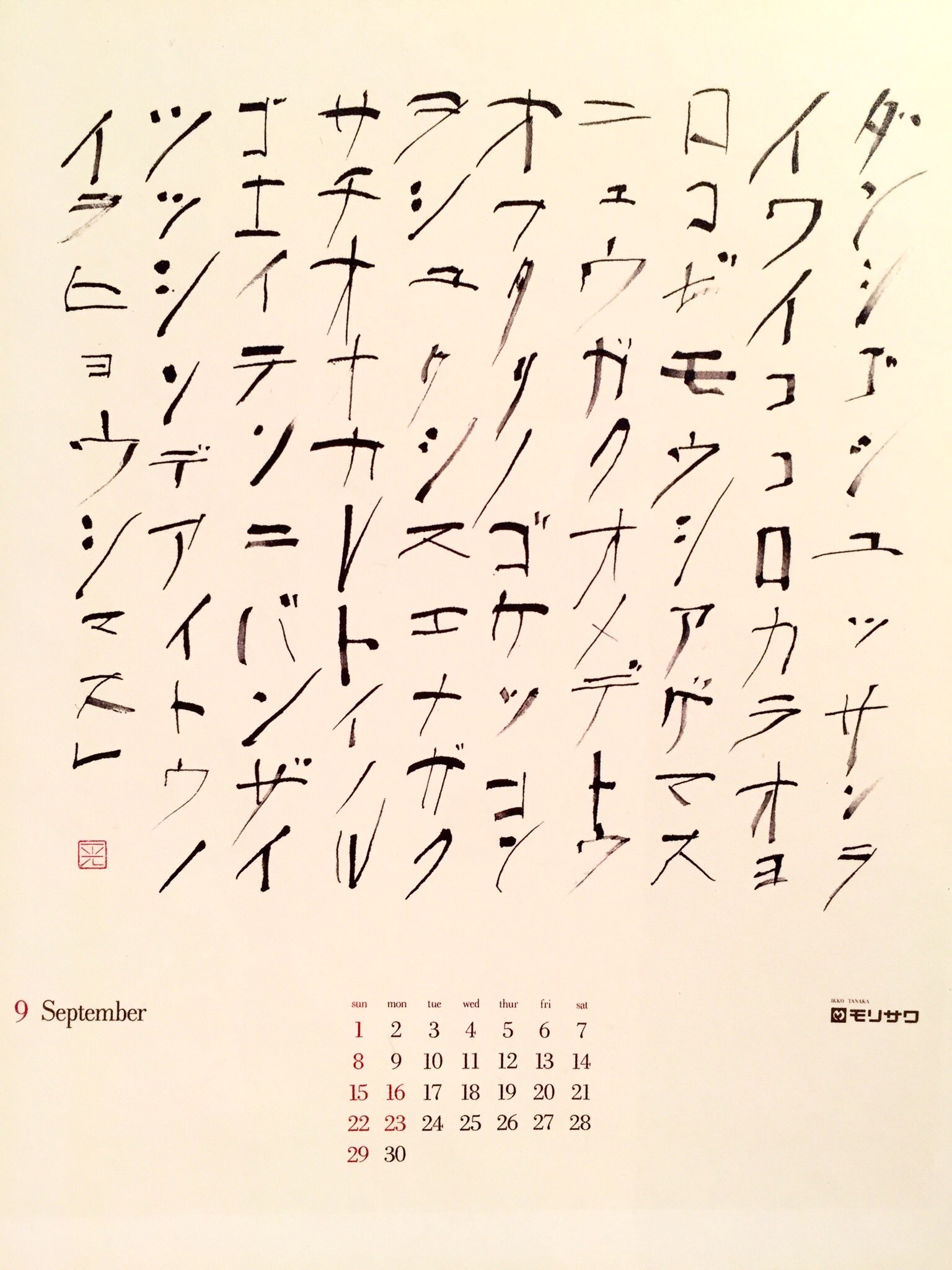

Ikko Tanaka, calendar for MORISAWA, 1973 via @telephant73

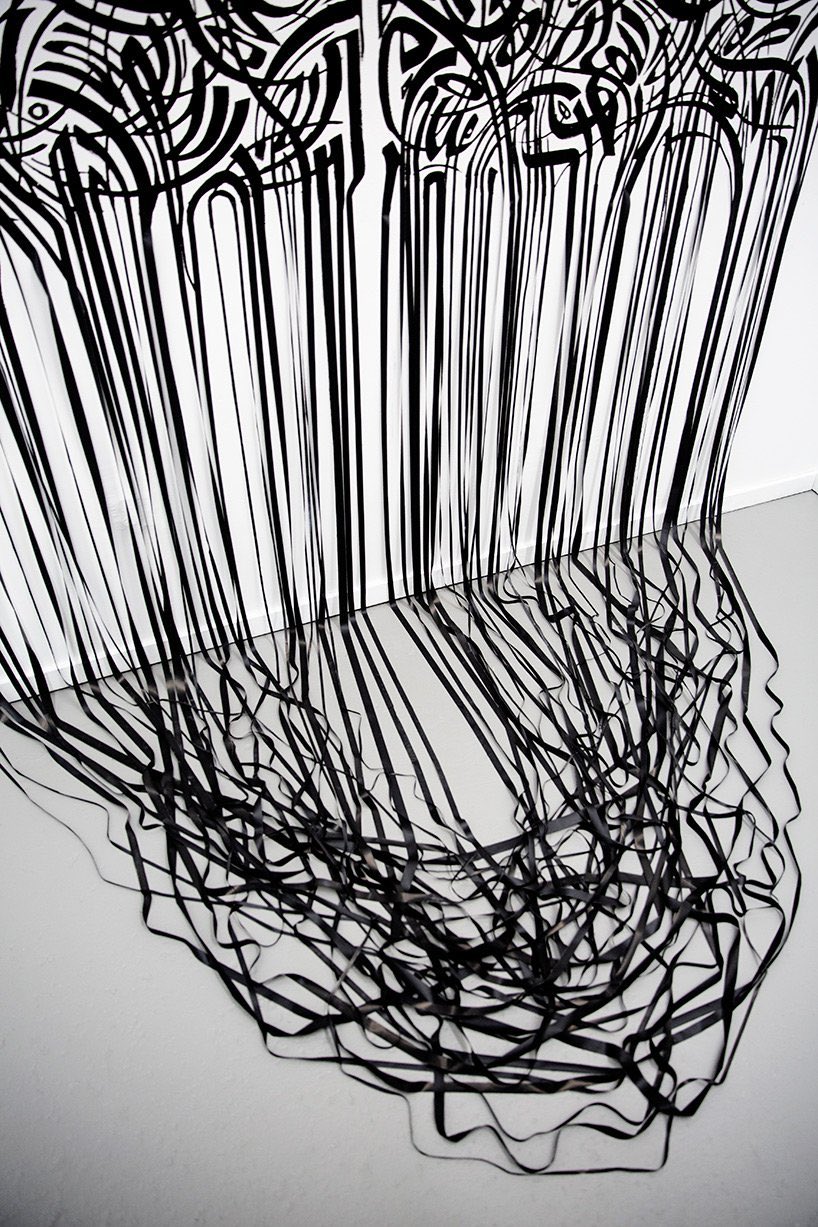

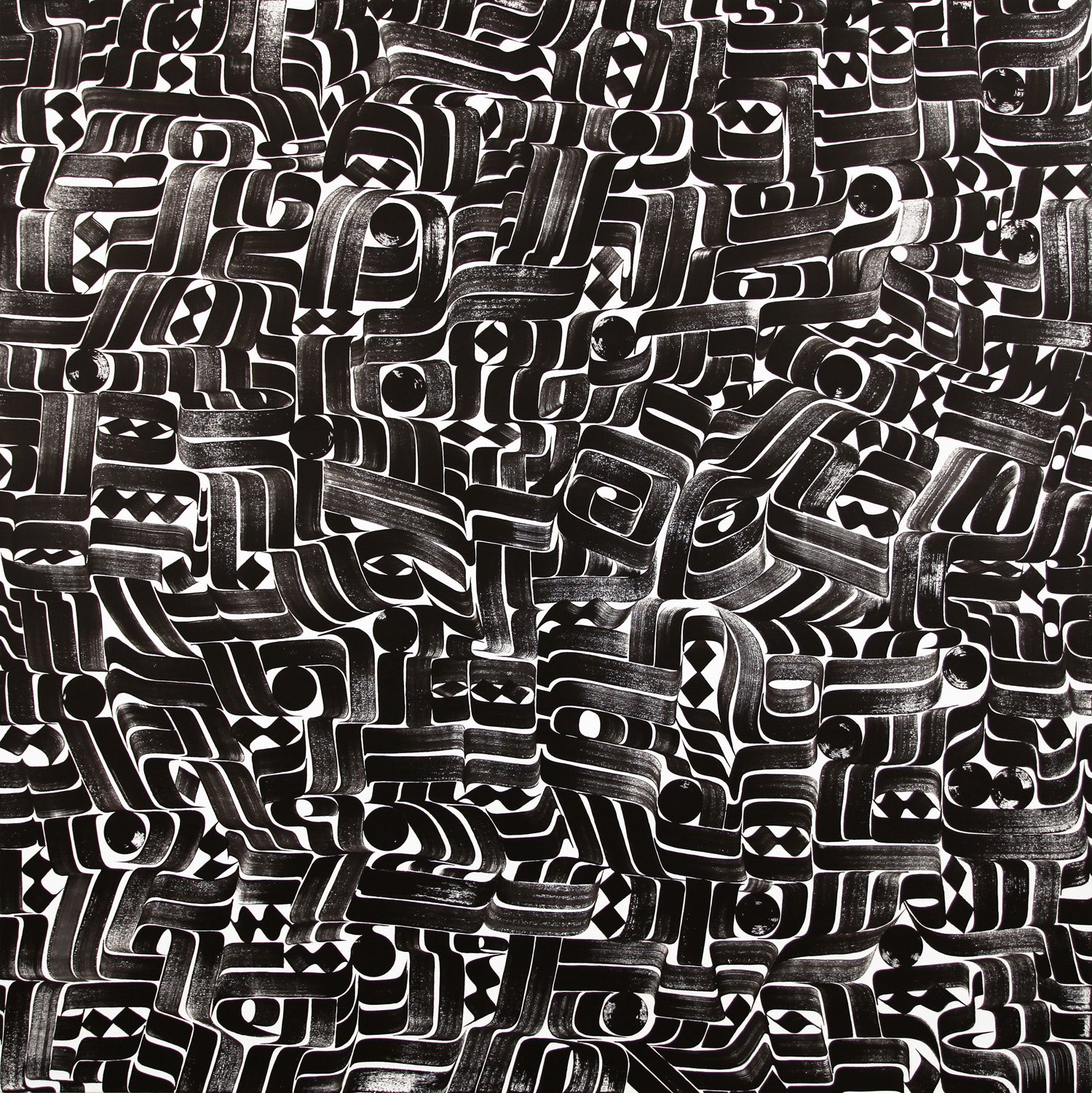

Romon K Yang Ink on Acrylic 2013 Diluvium via @Dazarbeygui

Edward Gorey via @AliceFukushima

John Furnival, Openings Press, Rooksmoor House, Woodchester Gloucestershire, 1972 via @Dazarbeygui

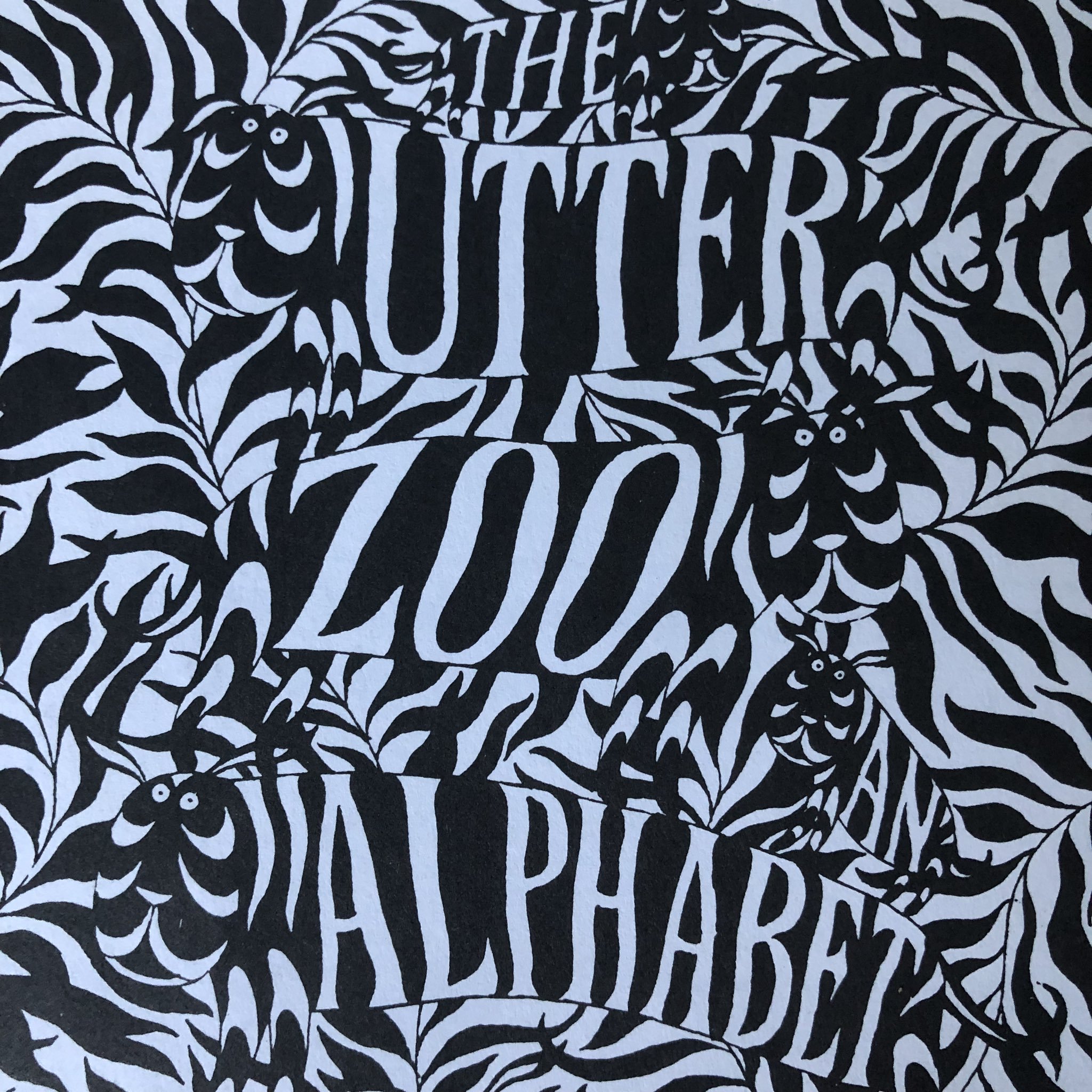

Book jacket hand lettering by @DesignQuay circa 1980s via @Patrick_Myles

Slider images: Leonardo Da Vinci's ink (and pen) drawings (image via RoyalCollectionTrust) inspired Parachute to release PF DaVinci Script Pro. Designed by Panos Vassiliou and Dimitris Foussekis for Parachute, PF DaVinci Script Pro is based on DaVinci’s own handwriting. This great Italian artist and perhaps the most diversely talented person ever to have lived left us with unique writing (used to write from right to left), which we have tried to decode and simplify with PF DaVinci Script Pro. Many of these letters are free interpretations and do not stick to the original forms. This typeface comes in 2 different styles: Regular and a more informal style called Inked. The all-new “Pro” version supports all European languages including Latin, Greek, Greek Polytonic and Cyrillic. It comes loaded with many stylistic alternates in all languages. More on this font here.

Tags/ origins, gutenberg, printing, greek, letterpress, design museum, india, sustainability, ink, eco-friendly, china, egypt, font sunday, fossil fuels, roman, material, xerox, scribes, guerino sacripante, vegetable-based ink, green, uv ink, soy-based ink, eco-solvent ink